Unity Housing Unit

Takeaways

Takeaways

- Recognize the vital roles that safe and supportive housing play in wellbeing

- Discuss the characteristics and values of best practice as reflected in this module

- Recognize the value of stakeholder engagement and flexibility in a successful supportive housing model

Components

Components

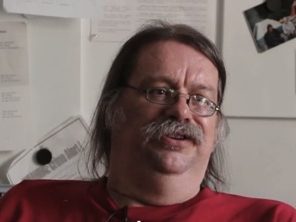

This component is this 10-minute video created by community expert Alex Verkade about Unity Housing, a resident-run housing project in Vancouver. An additional component is the text of the conversation between Verkade and senior project research assistant Christie Wall about his involvement with History in Practice and his hopes for his film.

Evaluating the Components

Evaluating the Components

- Component Evaluation: Create a Commercial – 45 minutes

- Component Evaluation: Themes and Analysis – 30 minutes

- Component Evaluation: Role Play – 30 minutes

Learning Lens

Learning Lens

What would happen if people with psychiatric diagnoses got to design and run their own housing programs? History in Practice Community Expert Alex Verkade had some good answers to this question because he helped create Unity Housing, a Vancouver-based housing organization. His 10-minute documentary, created with the help of UBC film student Alex Poutianinen, shows the inner workings of an innovative and successful model of community housing run by and for people with mental health difficulties. The film helps future mental health practitioners understand how stakeholder engagement makes a difference and underscores the value of the system that provides clear expectations and flexible solutions to help tenants remain housed.

Components in Context

Components in Context

This component illuminates the secondary benefits of good practice models.

Housing as a social, cultural and economic right was recognized in the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1976 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Canada voted in favour of these proclamations, but it does not currently have a national housing strategy. At present, most Canadian housing policy is not based on the idea that adequate housing is a human right, nor does it take into account the profound personal importance of having, not a house, but a home. Given their social and economic marginalization, it not surprising that housing deficits disproportionately impact Canadians living with mental health difficulties.

Just like their fellow-citizens, Canadians with mental health histories value choice, privacy, safety and self-determination in where they live and the shape of their home environment. In the immediate deinstitutionalization era, discharged patients often ended up in the seedy, for-profit boarding houses described by Torontonian Pat Capponi in her memoir Upstairs in the Crazy House. Today, there are three broad categories of housing available to people within the mental health system: residential housing in a group setting; supported housing within self-contained units; emergency housing in specialized mental health facilities, hostels or shelters. It is certain that Capponi would not use the descriptors privacy, safety, autonomy, choice, or control to describe the Parkdale boarding house in which she found herself in the late 1970s. But do those words match current housing options offered to consumers of mental health services?

“Housing First” is a recovery-oriented approach to housing aimed at people living with homelessness, addictions, and mental health difficulties. This approach to housing is based on the premise that providing hard-to-house individuals with safe and appropriate housing empowers them to begin to rebuild their lives. Emphasizing client choice and self-determination, and working to put into place housing, clinical and community and social supports, Housing First projects in Canada and elsewhere have had considerable success over the last few decades.

Useful material on housing and mental health can be found at: The Homeless Hub, a solution-oriented research site; The Mental Health Commission of Canada: Right to Housing.

Français

Français