Components: Moyra Jones – Self-Guided Learning

Components: Moyra Jones – Self-Guided Learning

Timing: 60 Minutes

Mode: In-class; Online

Innovation is a process that involves taking a new idea and giving it value, but it is also about recognizing moments and situations where change is possible, and working with established components to give them additional worth. Successful innovation involves delivering a product that is both helpful and meaningful to the people who will use it, a process often engages multiple actors and organizations. In order for innovation to bear fruit, stakeholders need to have a shared creative mindset and an acceptance of the potential for change. Today, with concerns about delivering care to a growing population of ageing Canadians, the notion of innovation in dementia care is particularly timely.

Ideas about innovation are most often employed in creating business models, but this unit tells the story of an innovation that gave new value, not to a cell phone app, but to the lives of elderly people with dementia and the practitioners who worked with them. Moyra Jones (1936-2015) was an important Canadian innovator in dementia care and rehabilitation therapy. Most well-known for the GentleCare approach to dementia care that she developed and marketed across North America and Europe, Jones began her work in Vancouver in the 1970s. As the video components presented in this lesson explain, Jones led a team of practitioners at Valleyview Hospital, BC’s provincial geriatric mental health facility, in the creation of an innovative model of treatment that brought together medicine, rehabilitation and the creative arts.

These self-guided resources are well suited for flipped classroom use with an in-class or online discussion or learning activity. Working in class or online, instructors and learners can select resources that suit the time available and a focus that fits teaching requirements. Ask students to use the following questions to guide their exploration of these components:

- What was Jones’ vision of best practice in dementia care, and how did her commitment to “making life happen” support a paradigm shift in the field?

- Innovation is about vision and What does it mean to support innovation as a leader, and what are the key personal and professional strategies that Jones employed?

- How did Jones’s social location and her professional credentials and experience in the health care system give her credibility to innovate at Valleyview?

- What does the Valleyview story tell us about innovation as a process (sometimes difficult and challenging) and about seeing opportunity in crisis?

How the story began….

In 1974, when Moyra Jones took the position of head of rehabilitation services at the George Derby veterans’ rehabilitation facility in Burnaby, BC, gerontology was a marginal field of study. In mental health terms, the aging brain and the elderly psyche were regarded as weak, the former in danger of succumbing to what was then known as senility, the latter prone to loneliness, lowered self-esteem, loss of self-confidence and feelings of redundancy.

Faced with a residential population of elderly men, the majority of whom had worked in BC’s remote forests and mines, Jones understood that standard recreation and rehabilitation activities like woodwork, painting, bingo and sing-songs were unlikely to be successful. Instead, she set in place a rehabilitation program that aimed to match the life histories and personal identities of George Derby’s residents, taking retired pilots to the annual Abbotsford Airshow and bringing in mineral samples for former prospectors to classify and sort. Highly organized and energetic, Jones used funding from local branches of the Canadian Legion to buy equipment and the voluntary labour of legion members to run an ambitious program of institution-community special events and resident outings.

Jones was adept at locating and inspiring like-minded allies in the workplace. Listen to Joy Fera, recreational therapist at George Derby, describe how Jones brought her on board with plans for George Derby and their move to Port Coquitlam’s Valleyview Mental Hospital.

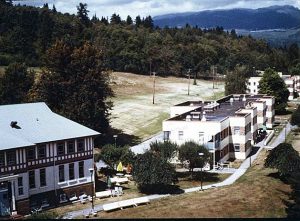

As Fera describes, in 1978 Jones was hired as Director of Rehabilitation Services at Valleyview Hospital, a large geriatric unit on the site of the province’s Riverview Hospital in Coquitlam.

Upgraded and modernized following World War Two, Valleyview’s operations were spread over eight buildings on the hillside facing southwest toward the Fraser river, and included an infirmary and admitting building with four wards for acute and chronic cases. Administratively separate from Riverview’s general wards and out-patient services, from the mid-1960s Valleyview administrators and staff were guided by broader trends toward psychiatric deinstitutionalization, attempting to use patient assessment, rehabilitation therapy, social work techniques and new “tranquillizing medications” to provide early treatment and discharge for patients who would formerly have become chronic, long term residents.

Music therapist Doreen Alexander, the first in her field to work at Valleyview, came to Valleyview shortly before Jones took up her new position. Listen to Alexander describe Valleyview and Moyra Jones:

Elements of the program that Jones would spearhead at Valleyview were in place when she arrived, but this was nevertheless a unique career opportunity in geriatric mental health. No other North American psychiatric facility had specific institutional provision for aged patients or an interest in creating an active psychosocial treatment program for this client group. The next decade would bring the “discovery” of Alzheimer’s disease as a major medical and social catastrophe and the creation of local and regional Alzheimer societies, but dementia care was still in its infancy in 1978. Jones was invited to lead a rehabilitation team that would work alongside the medical professionals as equal partners in delivering geriatric mental health care.

Multidisciplinarity and shared authority were at the heart of Jones’ vision for Valleyview. In her new treatment model, rehabilitation would encompass the standard rehabilitation therapies of occupational and physiotherapy – long established at Valleyview – but also the barber and the beautician, the chaplain, and a new group of re-recreation and music therapists. Importantly, it was decided that members of Jones’ rehabilitation team and Valleyview medical staff would have formal input in determining patient treatment plans. But there was resistance to this change. Jones’ tactics for dealing with opposition included educating medical staff with demonstrations and in-service training and, on occasion, terminating rehabilitation services on wards with intractable old-guard medical staff. Listen to Doreen Alexander and fellow music therapist Kerry Burke describe the first challenging efforts to create integrated mental health teams that would bring together medical staff and rehabilitation staff:

A charismatic personality, Jones was an excellent recruiter. She soon began broadening the scope of the Valleyview program, bringing in new music therapists, a volunteer coordinator, and her friend and former George Derby colleague Joy Fera. Jones courted colleagues with educational credentials who could match her breadth of vision and commitment to the work underway at Valleyview. Joyce Wright, who became a lifelong colleague and friend, describes how Jones convinced her to come on board and build the volunteer program at the institution into a large workforce that provided important links to the larger community. Why do you think Joyce Wright ended up saying yes to Moyra Jones?

For Moyra Jones, rehabilitation therapy offered elderly people quality of life and a sense of affirmation and personhood in a society that devalues its older citizens. Coming out of professional training at the University of Toronto’s joint Occupational Therapy/ Physiotherapy program likely gave Jones an affinity with multi-disciplinary approaches to rehabilitation and healing. And by the time she reached Valleyview, Jones also held a fervent belief that the rehabilitation professions were fundamental to good mental health treatment and care – not just for the elderly, but across the life cycle. As Kerry Burke explains, this was about seeing the social as potentially more important than the medical, a radical view indeed, and one that he sees at work in best practice elderly care facilities today:

But positioning the social as equal to the medical in a care model for dementia care, continues to be a matter of debate in the field. Many researchers stress that focusing family caregiver stressors, or on a search for “the cure” to Alzheimer’s disease, means that the needs of people with dementia are being ignored. At Valleyview in the 1970s and 1980s, psychiatric nurses who trained in a medical model of mental health care and treatment found it difficult to accept the new and promising practice of music therapy. Innovation requires demonstrating the value of new ideas and new methods, particularly in field of dementia care where ageism and our cultural fetish with cognition devalues elderly patients. Yet as Doreen Alexander recounts, changes in attitudes and practices did take place at Valleyview, and pivotal “breakthrough” moments at Valleyview still stand out clearly in her memory. What is Alexander’s “breakthrough” moment, and where can we still see inherent professional ageism in her account?

Jones had studied music seriously as a child and young adult in Ontario, so music therapy spoke to her as a treatment option in her work. Serendipitously, North Vancouver’s Capilano College (now Capilano University) graduated its first class of music therapists from a new diploma program in 1976, two years before Jones started at Valleyview. The Lower Mainland, with its substantial population of elderly people, was an excellent location for developing professional opportunities in music therapy for the aged. Over time, Moyra Jones came to believe that music therapy was the most promising practice for elderly dementia patients, and Valleyview became the model of best practice in geriatric music therapy in the province. The relationship between Capilano’s music therapy program and the aspirations of Jones and her rehabilitation team at Valleyview demonstrates the importance of recognizing and acting upon good timing, but also appreciating the potential of inter-institutional synergies. Listen to Liz Moffit, an early Capilano graduate and longtime instructor in the program, explain the background and orientation of the BC program and the importance of the link with Valleyview:

What makes music therapy such a promising practice in dementia care? Practitioners have long identified the role of music in fostering memory, movement and sociability, but recent studies also demonstrate that critical role which music can play in facilitating the activities of daily living for people with cognitive difficulties, arguing that music should be fully integrated into the fundamental routines of long term care facilities, for instance. By opening up a practice space for music therapy at Valleyview and by using her professional authority to promote the work more broadly, Moyra Jones helped demonstrate its utility in geriatric mental health when music therapy was still a marginal rehabilitation profession in English Canada.

Music therapists at Valleyview were therefore working on the frontlines of promising practices in dementia care, using the creative arts to craft a model of care that cast the practitioner as a friendly ally rather than a figure of authority and allowed patients to remember the contours of their lives and their personhood to emerge. Listen to Doreen Alexander explain some of the elements of therapeutic practice in music therapy at Valleyview:

There is a professional politic to institutional innovation, where change needs to work in the interests of all stakeholders. Kerry Burke found that his most successful Valleyview music therapy venture was a cumulative sing-along. Nursing staff supported this activity because it fit with demands of their work and linked back to established institutional practice.

What was it about Moyra Jones that inspired others to work with her? Former colleagues describe Moyra Jones as kind, fun and ferocious, a visionary mentor, and a person who pulled you into her plan but let you run with your own ideas. Operating in an old-guard health care institution in an era when middle class women were still maneuvering their way into the professional workforce, Jones set high standards for her team. But she also got to know them as people, helped them develop as practitioners, and shielded them against the judgments of the hospital administration. Listen to Joy Fera, Joyce Wright and Liz Moffit sketch out their memories of Jones as a visionary colleague and community builder, a professional role model and a mentor:

Sometimes history lets you get lucky. Joyce Wright shared more than her own memories. She retrieved a box of old video tapes from her basement, giving us access to footage of Moyra Jones leading a 1990s workshop. At Valleyview and in the decades that followed, Jones worked on the frontiers of dementia care, in Canada and internationally. She was a leader and an innovator, passionately engaged in psychosocial gerontology and committed to creating humane and helpful models of dementia care. Listen to Jones talk about her vision of good dementia care after 25 years in the field. Then reflect on comments by Joyce Wright and Liz Moffit about Jones’s contributions to more informed and compassionate attitudes and practices in the field. What does Jones’ presentation tell us about using self-knowledge and self-awareness to select a career path or field that challenges us to be our best professional selves?

Français

Français