The Doreen Befus Story Unit

Takeaways

Takeaways

- Recognize the historical role of medicine, science and the law and their institutions in violating the human rights of mental health patients

- Understand the danger of unchecked professional power and authority as evidenced in the theory and practices of eugenics

- Appreciate the possible consequences of professional practice that negates individual autonomy and agency

- Grasp the importance of seeing beyond diagnostic labels

Components

Components

This unit contains a powerful set of components: letters written by Doreen Befus, a target of eugenicists who became an activist, a sterilization timeline setting Doreen’s life alongside eugenicist thought and policy, official government reports detailing the practice of eugenics, and the insights of academics looking backward to these profound past injustices.

We provide a sample of historian Erika Dyck giving a biographical context to Doreen’s institutionalization below, but educators and students can find the whole set in Components: Self-Guided 1 and Components: Self-Guided 2. Transcription

Evaluating the Components

Evaluating the Components

- Components: Self-Guided 1 – Sterilization as Law & Practice – 45 minutes

- Component Evaluation: Self-Guided 2 – Doreen Befus Story – 30 minutes

- Component Evaluation: Sterilization Timeline – 30 minutes

Learning Lens

Learning Lens

This unit weaves together two connected storylines – the first of eugenics victim and disability activist Doreen Befus and the second of Alberta’s sterilization program, in place from the 1920s to the 1970s. A powerful and provocative set of components direct future mental health practitioners backwards through history to examine how medicine, science, and the law were utilized in particularly unjust ways in the service of “good” mental health. Students will learn how sexual sterilization law came to be seen as positive mental health policy to prevent “undesirable” children and “unfit” parents. Befus demonstrates the resilience and personal courage that is necessary to overcome a stigmatized medical diagnosis and medical label. It is through working with this kind of patient-centred material, and developing a capacity for respectful listening and ability to see beyond the limitations of labels, that the patient-practitioner partnerships that our community experts envision as an optimal practice model will emerge.

Many sterilization victims have been silenced by history, but two Canadians who study this difficult history have helped us tell their story. Claudia Malacrida, a sociologist at the University of Lethbridge, and Erika Dyck, a historian at the University of Saskatchewan, shared insightful audio commentary on sterilization and the lives of Befus and other women and men who were sterilized. Instructors and learners can make use of a historical timeline that maps Befus’ story onto the global history of eugenics, analyze the ideas behind Alberta’s 1928 sterilization legislation, examine how the province’s Eugenic Board operated, and learn about how this government program impacted the lives of individuals who were sterilized.

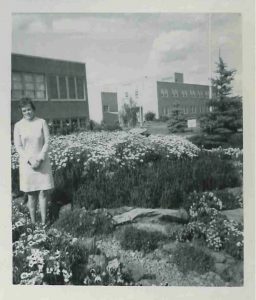

The woman in this 1960s snapshot is Doreen Befus, posed standing in front of an institution in Red Deer, Alberta. Doreen spent much of her life in institutions. Born in 1926, Doreen grew up first in foster homes and then, later, in Alberta’s Provincial Training School for Mental Defectives (PTS). Classified as a “Moron” and placed under the care of the PTS at the age of seven, Doreen was a candidate for sexual sterilization under Alberta’s Sexual Sterilization law. At the age of 18, she was brought before a panel of men, called the “Eugenics Board,” who decided that Doreen should be sexually sterilized so there would be no chance that she could bear children. The procedure was never explained to her nor did the Board seek her consent.

Doreen was a unique and remarkable person – a caregiver, an activist, a writer, a friend, a sister and an aunt. But the medical label of “moron” overshadowed these more important designations for most of her life, and her life story intersects with difficult histories of sterilization, eugenics, institutionalization and deinstitutionalization. In this fashion, Doreen stands in place for the thousands of unnamed patients in the Alberta Eugenic Board Reports that are used in these teaching resources, illustrating how many powerless individuals were controlled and coerced by early twentieth-century laws and procedures designed to “protect” the Canadian nation from those deemed mentally or morally “defective.” Students and instructors who wish to know more about Doreen can visit Erika Dyck’s Doreen Befus Exhibit on the After the Asylum site.

As the work of Malacrida and Dyck demonstrates, eugenicist ideas and the practice of forced sterilization are challenging historical topics. But these are not subjects that can be jettisoned to the historical scrapyard of junk science and regressive public policy, for the eugenicist mindset still lingers in professional practice and mental health provision. To give one example – in DSM-5 (Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition), the bible of current mainstream mental health practice, hoarding, persistent irritability in children, and grief at the loss of a loved one are presented as clinical categories, demonstrating the continuing power of normative social expectations in the mental health world. Like the DSM, the history of sterilization in Canada compels us to consider the immense and lasting power of medical labels and classifications.

The historical material presented in this lesson transcends the past/present divide, helping students today to appreciate the importance of addressing patient-practitioner power imbalances and the need for respectful communication and informed compassion. The dubious science of eugenics, and the labels which its practitioners used to define people like Doreen, illustrate the danger of attitudes and practices that categorize mental health patients as aberrant medical cases or broken people rather than as individuals with desires, gifts, goals and opinions. To support safe and effective learning, educators new to this material need to study and implement Mad School’s Anti-Oppression Statement.

Components in Context

Components in Context

Sir Francis Galton, an Englishman and cousin of Charles Darwin, created the pseudo-science of eugenics in the 1880s, a school of thought that regarded the human race as a vast breeding stock. For eugenicists, reproduction and the fate of the nation were inextricably entwined, for eugenicist theory categorized an individual as either “superior” and a worthy citizen, or “unfit” and a liability to the nation. The ranks of the unfit included many labelled “feeble-minded” – often a designation shaped by class, race and moral judgement – and sterilization was considered necessary to cull such people from the national breeding stock. As the Sterilization Timeline shows, professional and societal support for eugenics programs was a global phenomena: in 1933, for example, both the Liberal government in British Columbia, Canada, and the Nazi Party in Germany passed sterilization legislation.

Until the time of World War Two, eugenics was considered good science and garnered strong levels of support from Canadians. Eugenic sexual sterilization was supported by those we might consider unlikely promoters of such laws: first-wave feminists, health professionals and politicians. Luminaries in the Canadian medical establishment who were closely connected to the eugenics movement included Dr. Helen MacMurchy, famous for her Little Blue Books and other maternal health initiatives, Dr. D.K. Clarke, first professor in the University of Toronto’s Department of Psychiatry and Dr. Clarence Hincks, psychiatrist and founding director of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene (later the Canadian Mental Health Association).

Français

Français