From Stigma to Action Unit

Takeaways

Takeaways

- Understand the importance of adequate personal and systemic support in ameliorating discrimination and marginalization in mental health

- Appreciate the role of empathic knowledge informed by lived experience in fostering successful advocacy and activism

Components

Components

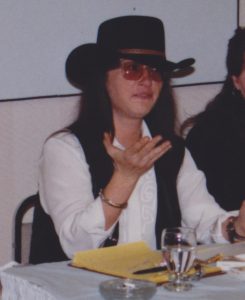

The components for this unit are frontline stories of marginalization, discrimination, and nascent activism by Pat Capponi – a canny activist and a powerful communicator and canny activist. Download vignettes from Capponi’s 1992 memoir, a 1980 newspaper article, and listen to these audio segments from a 2009 oral history interview.

Mice infestations in the larder and the bedroom fires where Capponi was left wondering, “Did everyone get out alright?”

Early tactics Capponi employed to pull media cameras into the boarding houses and push the government into action.

Evaluating the Components

Evaluating the Components

- Components: Self-Guided Learning – 35 minutes

- Component Evaluation: Capponi’s Journey – 30 minutes

- Component Evaluation: Getting to Activism – 20 minutes

Learning Lens

Learning Lens

In the late 1970s Pat Capponi was released from a Toronto hospital psychiatric ward into the community of Parkdale. She went to live in a local boarding house, one of many former grand homes in the area that had been converted by private landlords into housing for psychiatric patients. Capponi’s initial reaction to her fellow boarding house residents was fear and repulsion, but she became an empathetic observer of impoverished people struggling to adjust to community living without adequate supports. Educators will find support for teaching this unit effectively in Mad School’s Anti-Oppression Statement.

The trajectory of Capponi’s life was different from her fellow boarding house residents, many of whom died in the decade following her boarding house stay. Capponi did not just survive; she emerged as a community activist and political force in Toronto’s social justice scene. She also wrote about her experiences and the people who were part of her boarding house life in the 1992 book Upstairs in the Crazy House: The Life of a Psychiatric Survivor.

Capponi’s honest description of the disgust and revulsion that was her first response to other boarding house residents opens space for students to evaluate their own reactions to mental health patients and to consider how we “other” those who appear to be different from us. Capponi’s subsequent career as a community advocate and activist delivers a compelling message about the power of bringing together experiential insights, analytical understandings, and successful activism. The past-present attributes of these components are also illuminating. Passages from Upstairs underscore the harshly discriminatory practices and the piecemeal community support systems characteristic of the early deinstitutionalization era. Students will also recognize in Capponi’s narrative patterns and practices that are still evident today. Moreover, Toronto’s use of for-profit boarding houses makes clear to students that while the policy of the late 1970s and 1980s was deinstitutionalization, the practice was trans-institutionalization, with many former patients being shifted directly from one residential facility to another.

Components in Context

Components in Context

Pat Capponi’s activist memoir Upstairs in the Crazy House is not a local Toronto story. During the latter half of the twentieth century, in Canada and in other western nations, mental health care was transformed as patients were released from long-stay mental health facilities and relocated in the broader community. The motivations behind this policy shift were a complex blend of fiscal imperatives to fit costly mental health services into emerging welfare state funding structures, the availability of new pharmacological therapies, and emerging humanistic notions of social integration and patient rights.

Each of these “push” factors behind deinstitutionalization played out in cities and towns across Canada. Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood, where Capponi found herself, was a space infused with the politics of deinstitutionalization, labelled by many in the city as a “psychiatric ghetto”. Located midway between the Lakeshore Psychiatric Hospital, which closed in 1979, and the Queen Street Mental Health Centre (now CAMH), which down-sized in the same period, Parkdale was a first destination for many former patients seeking housing. Relevant statistics that are available to us about deinstitutionalization in this period are illuminating. During the 1960s and 1970s, seventy-five percent of hospital beds for mental health patients in the province of Ontario were closed and their occupants discharged. By 1980, it is estimated residential psychiatric beds in Toronto had decreased from 16,000 to 4,600 and approximately 1,200 discharged psychiatric patients were living in Parkdale.

Capponi’s boarding house was an early manifestation of trans-institutionalization, where former patients were redistributed across a series of smaller institutionalized settings. Many commentators believe that the term trans-institutionalization is a more accurate term than deinstitutionalization for describing the late twentieth-century paradigm shift in mental health provision. Markers of the systemic discrimination faced by former patients like those depicted in Upstairs in the Crazy House included: substandard housing; exclusion from the job market; social exclusion; lack of legal protection; poor health care and lack of basic necessities such as clothing, food and transportation.

Pat Capponi witnessed the introduction of a patchwork of new community services during her time in Parkdale. As was the case elsewhere in Canada, some of these supports were created by professionals, while others were initiated by concerned citizens or service users turned activists like Capponi. There was no overarching plan for what services would comprise the new mental health system for, as longtime psychologist Reva Gertein stated in her 1984 report of the Mayor’s Taskforce on Discharged Psychiatric Patients, “Neither my former colleagues or I ever fully appreciated the need for comprehensive aftercare services, including housing.” “Archway,” a walk-in storefront clinic in Parkdale and outpost of the larger Queen Street Mental Health Centre (now CAMH) offered counseling, life-skill training, day care and crisis intervention services. PARC (Parkdale Activity and Recreation Centre) opened in the former Lakeside Pool Hall and Bowling Alley in 1980, furnished in part with items from the Lakeshore Psychiatric Hospital. Houselink – referred to as “one ray of hope and stability” in Toronto’s bleak housing marker for psychiatric service users of the time – began to champion the right to safe, good housing of choice in 1976. Parkdale Community Legal Aid Services, formed in the same era, brought professional legal services to the service of poor and marginalized people of the area. Capponi herself began publishing Cuckoo’s Nest in 1979, a voice of Parkdale’s psychiatric survivor population speaking out to remove barriers of fear and difference and to tell the local community that this was their neighbourhood too.

Français

Français