The “Inexplicable Maze” Unit

Takeaways

Takeaways

- Recognize that the mental health system is structured to enforce racism, sexism, sanism, and other forms of oppression

- Understand the effects of trying to navigate a system that has been created and mobilized to oppress, negate, and abuse those who are already marginalized

- Appreciate the importance of intersectional resistance and activism

Components

Components

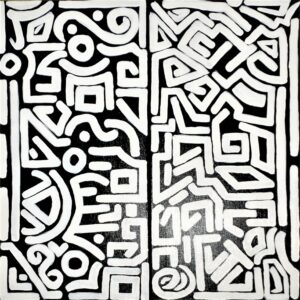

The component for this unit is a painting by Ashley T. called The Inexplicable Maze. This piece explores duality through her identity as a bisexual, Black biracial person diagnosed with bipolar disorder-type two. This maze-like piece is a puzzle that cannot be solved. This reflects the mental health system, which abstracts, abuses, and confines people who are already on the margins. An additional component is her artist’s statement and interview excerpts where she further unpacks her experience of being a Black woman committed to “shifting the narrative.”

The component for this unit is a painting by Ashley T. called The Inexplicable Maze. This piece explores duality through her identity as a bisexual, Black biracial person diagnosed with bipolar disorder-type two. This maze-like piece is a puzzle that cannot be solved. This reflects the mental health system, which abstracts, abuses, and confines people who are already on the margins. An additional component is her artist’s statement and interview excerpts where she further unpacks her experience of being a Black woman committed to “shifting the narrative.”

Evaluating the Components

Evaluating the Components

- Component Exploration

- Component Evaluation: Discussion based activity

- Component Evaluation: Knowledge Mobilization

Learning Lens

Learning Lens

Ashley T.’s “Inexplicable Maze” is an art intervention that invites viewers to consider the impossibility of navigating a dominant system that is simply not built for people whose identities place them at the intersections of multiple oppressions.

Problematic stereotypes about gender, race, and class have been incorporated into many psychiatric categories. Hysteria, for example, was a nineteenth-century label used to categorize – usually white – women exhibiting distress, while the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia were literally changed so that Black men engaged in protests during civil rights activism in the 1960s and 70s were disproportionately diagnosed and incarcerated in the mental health system. In the decades following World War II, lesbians and gay men found themselves enmeshed in punishing psychiatric regimes intended to “normalize” their sexuality, a pattern repeated in current responses to trans youth. Historically and to this day people of colour, queer folks, mad people, and people with disabilities have been abused and exploited by the very systems that profess to care for them.

Most educational materials about mental health have also been based on an unacknowledged white norm. This is the case with Mad School. With the inclusion of this unit, the contributions of BIPOC are “added”, but are they made central to how we learn about mental health? Ashley T.’s art and commentary invite us to consider these injustices, the enormity of the labour that is required to change them, and how this labour falls disproportionately on those most affected by them.

Facilitators using the unit should be equipped to teach from a decolonial, anti-racist and anti-oppressive perspective. To support safe and effective learning, educators new to this material need to study and implement Mad School’s Anti-Oppression Statement.

Français

Français