Ya’Ya Heit and Indigenous Mental Health Unit

Takeaways

Takeaways

- Recognize colonialism as a distal determinant of mental health and wellbeing and the relevance of the Indian Act to mental health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples

- Understand the impact of historical and legal forces on current material circumstances and mental health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples

- Appreciate Indigenous experiences and understandings of mental health and wellbeing

Components

Components

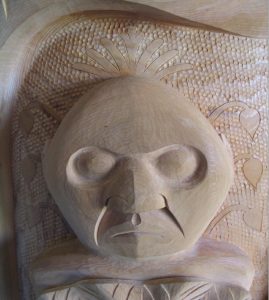

The components in Ya’Ya Heit’s unit are his powerful poetry and art which honour his brothers Yvon Michael Starr and Andy Clifton in the context of their heritage of a Gitxsan ancestry and membership in the house of Geel, the leading Fireweed clan house in Kispiox, BC. To the left is a detail from Ya’Ya’s totem “Me & My 2 Dead Brotherz,” and below is a verse from a poem he wrote in remembrance of their lives and deaths:

My bro Andy Clifton died in 1999

Am Hon wuz his real name

He wuz the first person I knew with AIDS I

wuz afraid back then

And so wuz he

Evaluating the Components

Evaluating the Components

- Components: Self-Guided – 15 minutes, flexible

- Component Evaluation: Visualizing Colonialism – 30 minutes

Learning Lens

Learning Lens

When compared to non-Indigenous settler Canadians, Indigenous peoples (as a population) live with significantly higher rates of poor-health. They die younger, live with higher rates of diseases and greater rates of poverty, experience more discrimination and social marginalization/exclusion, and have less education and employment. This means, very practically, that if you are an Indigenous person living with a mental health illness, you are likely ALSO living a life, as compared with a non-Indigenous counterpart with similar mental health realities, that is more challenging, more marginalized.

Ya’Ya Heit is a respected Gitxsan First Nations artist from the Skeena River country in northern British Columbia, Canada. For many Indigenous theorists, scholars, community activists – and even artists like Ya’Ya Heit, the increased burden or acuity of mental health illnesses MUST be understood as directly linked to colonialism in Canada. Colonialism, in this conceptual framework, is a ‘distal determinant’ of health and well-being. In other words, like the art of Ya’Ya Heit tells a story of, the mental health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada cannot be extricated from a history and ongoing unfolding of colonialism.

Ya’Ya Heit contributed pieces of his art to History in Practice for students to use as reflections on the connections between mental health and the difficult history of colonialism and Canada’s Indigenous Peoples. This idea is foundational to the resources which Ya’Ya Heit has shared, and is a critical concept for students to take away from this lesson. Instructors can use Ya’Ya’s poetry and art as a route into this analysis. To support safe and effective learning, educators new to this material need to study and implement Mad School’s Anti-Oppression Statement.

Components in Context

Components in Context

Ya’Ya Heit was born into the house of Geel, the leading Fireweed clan house in Kispiox. His Gitxsan name is Axgagoodiit and he has noted in interviews that politics and justice are a major influence on his work. Ya’Ya’s work has appeared around the world and, most recently, he is at work carving two panels for Osgood Hall in Toronto. A member of the Health Arts Research Centre’s (HARC) Advisory Committee in Northern BC, Ya’Ya’s longer biography is available here.

Mental health and wellbeing for Indigenous peoples in Canada– as the visual and literary art of Gitxsan Hereditary Chief Ya’Ya Heit makes clear – is, perhaps, even MORE complicated than for non-Indigenous settlers.

Before exploring this, however, it is worthwhile to make clear a few terms.

First, Canada’s constitution recognizes three distinct groups of Indigenous peoples: First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people. Second, these constitutionally recognized groups of peoples are, as with non-Indigenous peoples in Canada, remarkably diverse: they exist across vastly different geographies and hold unique and ever-changing sociocultural protocols and histories. Third, the processes of colonialism in Canada (which, most broadly, involved first deterritorializing First Peoples so that settlers could claim land and resources and then, secondly and still ongoing, efforts to ensure Indigenous peoples could not reclaim what was removed from them) have FURTHER categorized Indigenous peoples, most acutely under The Indian Act. The Indian Act, written into existence in 1867 in order to address “the Indian problem” (how to manage and govern what settler-colonial subjects thought of as unruly, uncivilized peoples who would likely soon be extinct) first defined what an “Indian” was (and was not), second, what responsibilities the state had towards those peoples, and third, what rights Indians had.

The Indian Act, with some modifications, still exits today – leading many Indigenous peoples (including Ya’Ya Heit, through his art), and especially First Nations people (Metis and Inuit people are not governed by the Indian Act) to argue they are governed differently, and indeed sub-standardly, than everyone NOT covered by the Indian Act. Being governed by the Indian Act does have very real outcomes for the everyday lives of First Nations. First Nations living on Indian Reserves – places the Federal Government first arbitrarily created and then designated First Nations to – live on lands that, despite existing within the boundaries of provinces, are deemed Federal Lands. This means that provincial jurisdictions – things like schooling and health care – are, instead, funded and administered federally. For many people living on Indian Reserves – like Ya’Ya does – this results in additional layers of bureaucracy and, indeed, unequal levels of funding as compared with people living off-reserve.

The Indian Act also classified Indians, the ramifications of which reach into today. For instance, the Indian Act defines some First Nations peoples as “Status Indian” and others as “non-Status Indians”. “Status Indians” are further categorized as 6(1) or 6(2) Status Indians, the outcome of the Federal Government retroactively granting status to Indians from whom they had removed it between 1867 and 1985. The thing is, if a 6(2) Indian (someone granted status AFTER 1986) has a child with a Non-Status Indian (e.g. the VAST majority of people in Canada and around the world), that child is no longer recognized as an “Indian” in Canada. Because the Indian Act grants a small number of rights to status First Nations peoples, including small amounts of additional healthcare and education funds and in recognition of having settled Canada and dispossessed the geographies original inhabitants, the fewer “status” First Nations peoples, the cheaper it is for the federal government of Canada.

Put into a “big picture” of Indigenous peoples’ health and well-being in Canada, the issue of classifying out of existence Status Indians is, arguably, part of an overall system that consistently marginalizes Indigenous peoples. This too is something Ya’Ya Heit’s art speaks about. For instance, in a recent CBC Radio Interview about a totem pole he is currently working on, Ya’Ya speaks about the pole being “a political statement on the Indian Act.” He sees the Indian Act as connected to the alcoholism, the health, and economic struggles in his community – all of which are linked to mental illness or well-being. Heit notes: “I’m thinking of a title for it … Who the Hell would want these chains?, the chains being the Indian Act. So I put myself in there again. And this time, I have my three ancestors up above me. They were free,” said Heit.“And so I struggle, and like my ancestors, I wish for a better tomorrow in Canada. But I don’t lose hope, because I have children,” Heit continued.

Français

Français